I’m dabbling a little bit in the start-up world (www.elipsystech.com), and enjoy reading books about the start-up journey.

One of my favourites, is a book called the: ‘The Lean Startup: How Constant Innovation Creates Radically Successful Businesses’ by Eric Ries (https://theleanstartup.com/book). From a start-up perspective it’s got some great ideas, but I figure it’s got just as much gold in it for coaches. I don’t think coaches are that much different from entrepreneurs and, in their work with athletes, there can be some advantages to taking a start-up approach to development.

Ries, defines an entrepreneur as “Anyone who is creating a new product or business under conditions of extreme uncertainty…” (p 27). If we replace ‘product’ with ‘athlete’, I can’t think of a better definition. There are so many unknowns in learning and development that the complexity of the process alone means coaches need to be able to find ways to navigate uncharted waters. You can use

ideas that have been proven before, but to have true success, you need to confront that uncertainty and create new ways of doing things.

The idea that “The goal of a startup is to figure out the right thing to build—the thing customers want and will pay for—as quickly as possible.” (p 20) completely aligns with the challenge that coaches face. You need to figure out the right skills to work on (prioritise) and the most effective/efficient way to develop those skills.

To do that successfully, coaches need to avoid the same traps that entrepreneurs avoid – “…many entrepreneurs take a “just do it” attitude, avoiding all forms of management, process, and discipline. Unfortunately, this approach leads to chaos more often than it does to success.” (p 15). One of the easiest ways for coaches to find themselves banging their heads against the wall when they tried the same thing and it doesn’t work, is to avoid any systematic, deliberate approach to the process of development. Mindless approaches lead to stagnation and disengagement.

Here’s a few more ideas that resonated with me and that coaches can use to create their own ‘coaching start-up’.

1. The “product” is the results of interactions and experiences.

Coaching is about more than just putting together a session plan that fills an hour or two of someone’s day. It’s about creating interactions and experiences that lead to change – as Ries puts it, creating “value” for people.

The goal of the coach is to develop the people-product by creating great experiences. This is what creates “value” in coaching. How you define value will depend on the level and type of athlete you’re coaching. In community sport, a good amount of that value should come from creating enjoyment. Whereas the value in elite sport tends to shift towards performance and results. Learning and development are timeless. They create value no matter what level you’re working at.

When you’re planning, don’t just approach a session with the intention of piecing together a series of activities that focus on skills. Consider how you can create and shape experiences that leave an impression. Experiences that lead to learning!

For example, rather than designing a session with tangible pieces in mind (e.g., we need to have a warm-up, we’ll do 3 stations for 10-min that focus on 3 different skills), think about how you want your athletes to come out of the session feeling. Do you want to boost their confidence? Include activities that they can do successfully. Do you want them to have an “A-HA!” moment? Make sure you’ve got some problem solving in place and are giving them space to fail.

Next time you put a practice plan together, think about how your athletes will be experiencing each part of the plan.

2. Validated Learning

One of the central ideas of the books is learning (surprise, surprise!). But not just any old learning. Something he calls validated learning.

What is validated learning?

“Validated learning is not after-the-fact rationalization or a good story designed to hide failure. It is a rigorous method for demonstrating progress when one is embedded in the soil of extreme uncertainty in which startups grow. Validated learning is the process of demonstrating empirically that a team has discovered valuable truths about a startup’s present and future business prospects.” (p 38)

What I love about this, is he frames learning as something that needs to be closely measured and assessed. We don’t just go out, do something, and pat ourselves on the back afterwards. If we want to make tangible progress towards our goals, we need put effort in to considering how we’re going to evaluate our work (how will we measure progress?) and making an honest assessment of that work (how do we know if it was effective?).

In sport, we tend to look at learning superficially. We assume that, just because we put in the time, we’ll get the results. But, if we’re not putting time into the right activities, we might not be heading the right direction.

This ties into another idea about validated learning that the book explores: value vs waste.

Ries is pretty ruthless in suggesting that anything that doesn’t create value is waste:

“…learning is the essential unit of progress for startups. The effort that is not absolutely necessary for learning what customers want can be eliminated. I call this validated learning because it is always demonstrated by positive improvements in the startup’s core metrics.” (p. 49).

Coaches need to be ruthless in how they evaluate where they’re putting in effort as well. I don’t know many coaches who complain about having too much practice time on their hands. If time is a scarce commodity, then we need to make sure we’re using it as effectively as possible.

This is why it’s so important to spend time at the front identifying priorities, determining what success looks like, and understanding how you’re going to evaluate progress. Investing even just a little more time working through these questions can help you get the most out of the practice time you’ve got and save yourself from frustration when things “aren’t working”.

3. Experimentation

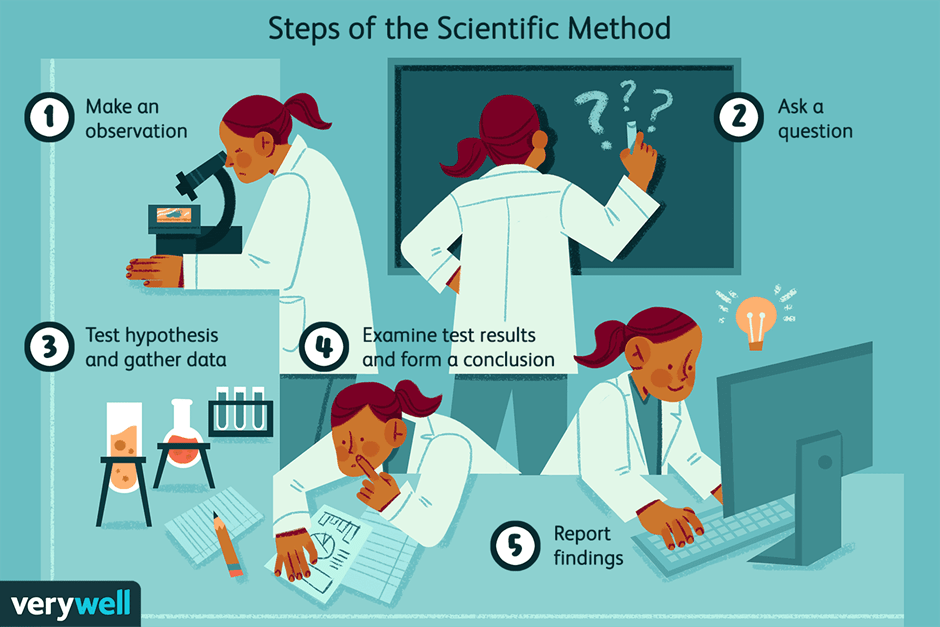

The last concept that I’ll hit on in this article is the importance of experimentation in the world of start-up. The argument is that start-ups need to follow the scientific method in their approach to business:

“Just as scientific experimentation is informed by theory, startup experimentation is guided by the startup’s vision. The goal of every startup experiment is to discover how to build a sustainable business around that vision.” (p. 57).

Replace ‘startup’ with ‘coach’ and the argument still rings true. I’ve often said that coaches need to approach development with the mind of scientist: develop a theory or framework for development, use that theory to guide your predictions, and then test, test, test!

When we link this idea to the concept of validated learning, experimentation doesn’t just mean trying a bunch of random approaches out and seeing what works. No. It means being very methodical and deliberate about what you will (and won’t) try, making educated guesses about the possible outcomes, and objectively assessing the outcomes (i.e., accepting that everything you try might not work, but knowing you approached it the right way).

This last point is what really matters. Inherent in this idea of experimentation, is the acceptance that not every experiment is going to be a success. Science, actually scientific publishing, is guilty of survivorship bias – there are hundreds of experiments that fail before one succeeds, but we tend to ignore that fact and focus on the successes.

This is something coaching, and especially elite sport, needs to get more comfortable with. If we’re going to be pushing the limits and innovating (like a start-up), we need to accept that some of the activities we try or new ways of communicating might fall flat. But as long as we’ve approached the problem the right way, that time isn’t necessarily wasted because we’ve improved our processes and have another datapoint to guide what we do next.

We need to normalize the right kind of failure, because as Ries puts it:

“…if you cannot fail, you cannot learn.” (P 56).